Recently, I saw a piece of a talk show in the Netherlands with some young environmental activists talking about climate change. One of them made clear that, according to him, it was legitimate to use violence (blocking roads or destroying a pipeline) when the violence against the earth will cause – in the end – thousands and even millions of people to die. He literally said this: “I think we have to reflect on what violence is. Is violence to blow up a pipeline? Or is violence not doing anything against the climate crisis, which will cause hundreds of millions of people to suffer and die? What is violence?”

Most comments below the video emphatically rejected both the declarations of the boy and the applauses he got, for “violence is never justified” (unless we’re talking about Ukraine, the brave Fanny Schoonheyt or the fearless Hannie Schaft, but we’ll just ignore them for the time being). Violence is never justified, according to politically correct Jan Smit.

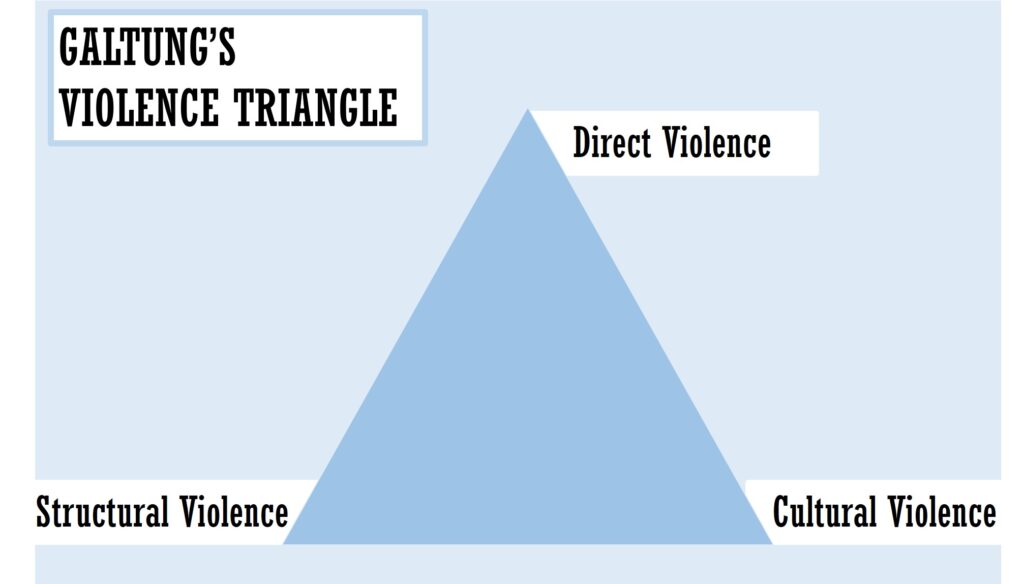

My mind immediately made the link to Johan Galtung’s theory about structural, cultural, and direct violence. According to this Norwegian sociologist and mathematician, one of the founders of peace and conflict studies, there are three types of violence that are interconnected, which is why they are usually represented in a triangle: structural violence, cultural violence, and direct violence.

Direct violence is physical or verbal violence, visible to anyone. Under the surface, there is structural violence and cultural violence. Structural violence comes from established power structures that exclude people from education, access to water, to culture, to housing, using repression and exploitation. Cultural violence is also called symbolic violence and is the legitimization of structural or direct violence, for example through racism or patriarchy. Cultural violence might not cause victims in a direct way but contributes to maintaining and justifying structural and direct violence. According to Galtung, it is not enough to silence the guns; if nothing is done against structural and cultural violence, then direct violence will, sooner or later, (re)appear.

I remember us (the FARC) talking on many occasions about structural violence, about how inequality, hunger, lack of water and poverty – “the structural causes of the conflict” – had to be resolved in order to be able to build peace and I recall the media labeling us as cynical. This kind of narrative was inadmissible, we were told. It was understood as if the Farc were trying to justify direct violence on our side (killings, kidnappings or attacks), while to us it was just an explanation of how we perceived our struggle and where it originated, and how there are different kinds of violence with no form of violence necessarily being worse or better than others.

My point is that people seem shocked by direct violence, as it is visible to the eye, while they care less about structural or cultural violence. The woman who shoots at her husband after years of enduring his physical and psychological violence is generally perceived just as wrong as domestic violence itself. Blocking a road because you are demanding a stop on fossil subsidies is “just as bad” as promoting fossil subsidies. Because people say it is not the way in which civilized people should respond to structural violence. Structural violence in the end may end up making more victims than any direct violence has ever done, but to most people that doesn’t matter. It is often long-term violence, it is not that clear who bears responsibility and neither is the number of victims. We don’t see it, we don’t understand it, so let’s ignore it.

In Colombia, the Misak indigenous community took down the statue of Sebastián de Belalcázar, a Spanish conqueror, in 2020. After centuries of structural violence against indigenous communities, many people in Colombia were shocked by such barbaric behavior from the Misak people. Public indignation was zero regarding structural violence against the indigenous: historic extermination and, today, racism. But when there is a response of direct violence, it is presented as an irrational event, vandalism for no reason. Again, the message is: “Yeah, of course we all know that racism is not ok, and we should work on that, BUT THERE ARE OTHER, MORE CIVILIZED WAYS, OF EXPRESSING THAT. You may peacefully protest, you may use the law, you may vote: these are the instruments we provide whenever you don’t agree with what we’re doing. Violence is not the way”. AS IF RACISM WEREN’T VIOLENT. AS IF POVERTY DIDN’T KILL.

As I am an ex-fighter of the FARC, whenever I write I need to include a disclaimer for people with reading comprehension problems. I am NOT saying that direct violence is a solution to problems. I am NOT saying that direct violence is legitimate per se or that I recommend it as a way of resolving problems. I DO say, with Galtung, that direct violence is a consequence of structural and cultural violence, and I DO say that I don’t see why direct violence is necessarily worse than structural violence (which ultimately can be the cause of so many disasters, floods, hunger, poverty, and deaths). To use direct violence is a choice, but to use structural or cultural violence is ALSO a choice, let’s never forget that. It is a choice made by people who hide behind curtains of laws, companies, bureaucracy, and political correctness.

4 Responses

Mooi stukje tekst om over na te denken!

Dat is fijn om te horen!

Super interessante materie waarbij ik blij ben dat je bij de FARC zat zodat je de tekst nog iets meer leesbaar maakt voor taal knobbels zoals ik haha. Ik snap je gedachten goed als activist. Als kleine ondernemer, natuur en cultuurliefhebber ben ik van mening dat er een limiet moet zijn aan macht en rijkdom. Ik denk dat dit jou ideaal dichter bij zou brengen en mijn frustratie van ongeremde groei misschien ten goede komen. Mijn personeel is mijn geld. Zonder hen ben ik niets. Met de huidige personeelstekorten vallen de slechte bazen gelukkig snel af. Tot de volgende blog. Gr Peter

Ik denk dat vandaag de dag steeds meer mensen – of het nou ondernemers, artiesten, onderwijzers of bouwvakkers zijn – bezorgd zijn over de aarde, over de toekomst, over het klimaat. Ik denk, met jou, zeker dat er een limiet moet zijn aan macht en rijkdom, of in ieder geval aan geldlust en machtslust, willen we een leefbare aarde hebben nog over een aantal jaren. Daar zijn we het iig over eens! Groetjes uit Cali, Colombia!